What overwhelms you about Rome once you overcome its first layer, the one of postcard and images from history books, is the extent of its proposal as a time witness. Where ever you have the chance to walk, the gaze runs into a quote carved in stone, a decoration, a lintel or a marble frieze that hides one, two hundred lives and a hundred re-uses, every street, every building, every corner seems to retain memories. For someone like me who loves the old stones, beveled porphyry and cooking smell that escape through the house blinds, the Testaccio area in Rome is a kind of heaven on earth.

The Testaccio district differs from other areas in Rome for maintaining over time its original popular spirit. It expands between Via Marmorata, the Aurelian Walls and the Tiber, in the shape of an a kind of regular quadrilateral, almost flat, except for its artificial Monte Testaccio, that used to be the largest landfill of Rome ancient port, the ‘Emporium, formed by the accumulation of earthenware vessels, named “testae” in Latin.

The number of stacked amphorae that shape the hill is estimated at around 25 million. The empty pitchers that contained primarily oil, were broken in pieces then neatly arranged in a stepped pyramid and sprinkled with lime to prevent the organic residues smell. The port Emporio was the final destination of all the goods and raw materials (apart from oil, they were primarily marble, wheat, wine) that were arriving by sea from the Ostia, and sailed up the Tiber river on barges pulled by buffaloes up to the year 1842 when they were replaced by steam trailers.

After 1870, the area was drained (despite being inside the walls, it was populated by poor farmers and shepherds, subject to the Tiber floods and infested by malaria) and urban reorganization allocates this land for industrial activities and “heavy” services such as railways, slaughterhouse, general markets, and gas factory.

Testaccio is a typical example of industrial urbanization, born as a residential settlement, separate but connected to the places of production. In the 1960s there began the decommissioning of large industrial areas that actually started in the postwar period with substantial abandonment of the river port, with the closing of the gasworks and the old slaughterhouse where today is located a section of the MACRO (-Contemporary Art Museum of Rome) and the headquarters of the Department of Architecture of the University of Roma Tre,

The process of modernization, has transformed many of the typical roman taverns into pubs, restaurants, and clubs but some still honor their tables with rigatoni con la pajata (rigatoni pasta with calf intestines), tripe, coda alla vacinara (oxtails), the dishes that in the old Testaccio tradition were made with slaughterhouse waste.

This neighborhood is a widespread museum: to explore it is a journey that spans all ages, from Emporium, remains of Imperial Rome to the Fascist buildings along with fascinating examples of industrial archaeology. the so-called English graveyard, the Cestia Pyramid and so much more, a wonderful melting pot that will make you love even more the city through a more popular perspective.

La Piramide Cestia

Imagine you are going to visit your friends in Rome, leave the underground and see in front of you, against a sky of a perfect blue, the silhouetted of a solemn white pyramid in the middle of city traffic.

This is the vision that you find yourself in front of the exit of metropolitan Pyramid Testaccio and right beside it, as if it was not enough, on its side, the equally solemn Porta San Paolo, one of the southern gates of the Aurelian Walls in Rome, among the most impressive and best preserved original doors of the entire city walls. At that moment it is inevitable to think: only here, in this city that never stops to amaze you, in a considered popular district you slam against the vestiges of an ancient world that in Rome never ceases to be present.

The Pyramid of Cestius was built by Caius Cestius as a grandiose burial around 20 BC, following the Egyptian fashion of the time. In fact, the presence of a monument in the form of a pyramid in Rome is probably due to the fact that Egypt became a Roman province a few years earlier, in 30 BC, and the lavish culture of this new province was becoming fashionable in Rome.

The Pyramid was built in just 330 days (not like nowadays that it takes forever to see the end of constructions) and it measures about 30 meters per side, almost 36 meters in height and was built from a coated concrete core of white marble blocks with a tiny burial bricks chamber in its intern whose cubic capacity is just over 1% of the total volume of the monument.

The Roman system of construction, however, was different from the Egyptian due to the use of concrete.

A comparison with the Pyramids of Giza reveals that the structural strength of the concrete allowed to build the Roman pyramid with a much more acute angle than the Egyptian ones and reached a greater height with the same amount of material. For centuries it was an enthroned detached structure located on the ancient “Via Ostiensis” until it was incorporated inside the defensive city walls built by Emperor Aurelian (A.D. 274-277).

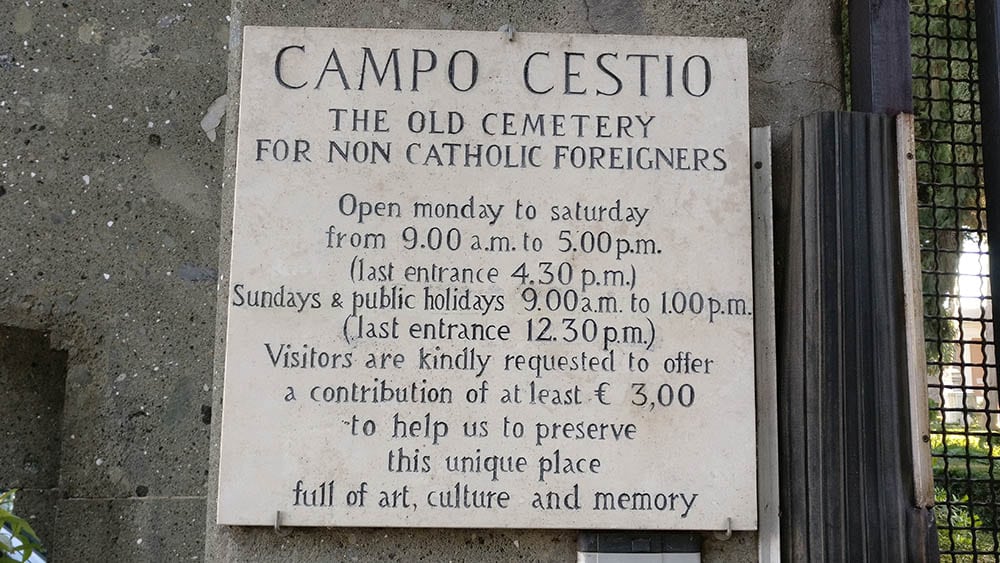

The Protestant Cemetery

If you walk around the Pyramid and take the first street on your left you will find yourself at the entrance of the Protestant ( or so-called English) Cemetery.

To step in this quiet and silent place you immediately feel surrounded by beauty and peace.

I personally love old cemeteries and whenever I have the chance, I try to spend time among the graves, reading the words engraved on the stones, trying to imagine the lives of the ones passed away. Every time I spend some time in Rome I come to this place that you shouldn’t forget to visit and look outside the city, its noise, and its chaotic traffic for a while.

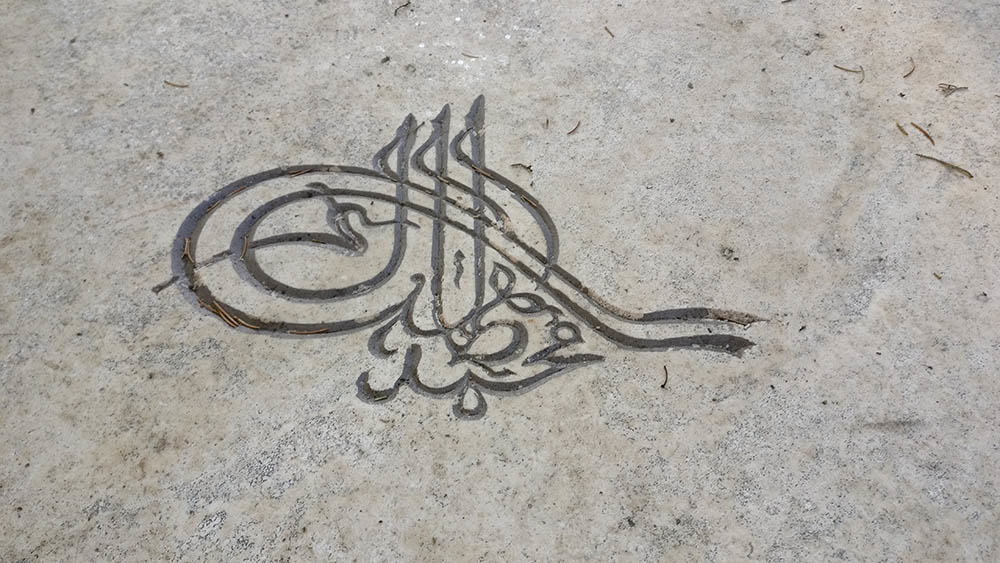

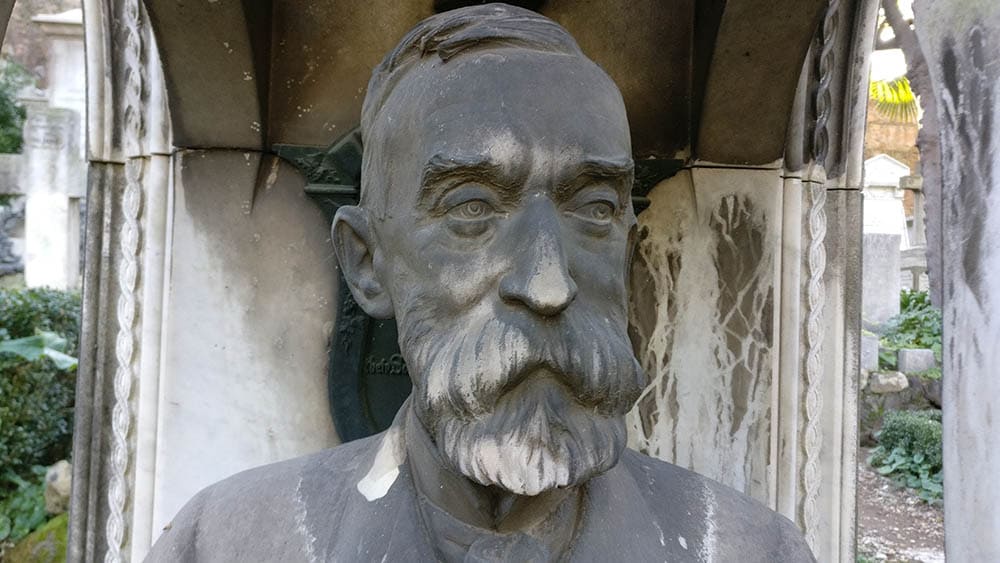

The population of the cemetery is exceptionally diverse, but also exceptionally rich in writers, painters, sculptors, historians, archaeologists, diplomats, scientists, architects and poets and some of them are worldwide famous. In addition to the significant number of Protestant and Eastern Orthodox graves, there you can find tombs that belong to other religions such as Islam, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. The inscriptions are in over fifteen different languages – Lithuanian, Bulgarian, Czech-Slavic, Japanese, Russian, Greek, and Avestan, and often engraved with their own characters.

It’s one of the oldest burial sites still in use in Europe since the beginning of its use dates back to 1716.

Since the rules of the Catholic Church forbade to bury non-Catholics in consecrated ground – including Protestants, Jews, and Orthodox – as well as suicides and actors, these people, after death, were “expelled” from the Christian community and buried out of the town walls (or just beside them).

In the 1700 and 1800, the Protestant Cemetery area was called “The meadows of the Roman people.” This was an area of public ownership, where it was grazing the cattle, it keeps the wine in cavities in the mount of the crocks, where the Romans went to recreation.

In 1671 the Holy Office agreed that the “non-Catholics”, who died in the city, should not suffer the humiliation of being buried together with prostitutes and sinners and they chose precisely that area which over time it acquired the status of the British cemetery, although buried were not only from the UK. It is significant that, at least in the older areas of the cemetery, there are no crosses, nor hints at an afterlife, because until 1870 these signs and inscriptions were prohibited by the ecclesiastical authorities upon the graves of non-Catholics deceased.

The “old part” is home to the two most famous tombs and the most loved by visitors, the twin stelae, one unnamed with the lira where is buried the English poet John Keats, the other, with the palette color of John Keats painter friend, Joseph Severn. Keats reached Rome in 1820 and died on February 24, 1821, at the age of 25. With his typically romantic sensibility, Keats was one of a hundred young Europeans, attracted by the irresistible beauty of this decadent city that came here from every corner of Europe knowing the risks of malaria or other epidemics that then raged over Rome.

The Post Office Building

While you get out of the Protestant Cemetery, still absorbed in the rarefied atmosphere you just left behind, you find right in front of you a bright, Fascist building that snaps you out of your dreamy mood. Once again the blue sky perfectly frames the Post Office building (1933-35) which is one of the main Roman Rationalist architecture of the ’30.

Rationalism was an international movement which focused on the need for order and logic and whose architectural style is the results of the application of rationality and perfect compliance of the building to its function.

Its author, Adalberto Libera (1903 – 1963), was the founder in 1926 of the Group 7 and soul of the Italian Movement for Rational Architecture (MIAR); he also signed among others, the Palazzo dei Congressi in Eur (1937-42) and the Villa Malaparte in Capri (1938-40). This is the architecture that is often present metaphysical paintings and is strictly connected with the space classical rules: place on a wide staircase as a classical monument, the Palazzo della Posta, with its strict symmetrical composition, based on geometric relationships of the golden section, was abandoned a few years ago and is still waiting for a new destination of use.

In my opinion, a strange misunderstanding between Mussolini and his architect made us enjoy the rationalistic architecture that was adopted by the regime to represent its arrogant power and yet today, deviated from its origin, shows us a beauty that in its austerity seems almost dreamlike.

The ex-Slaughter House

The walk in Testaccio soon takes you to the old Slaughter House, dismissed in 1975, that for almost a hundred years has provided the city of Rome of its butchered meat.

The complex covers an area of 25,000 m² and its main entrance carries on top of a front door arch,

the statue of a naked and winged young man, who is trying to have the upper hand on a nervous bull.

It could be the complex construction period (1888) or the habit of the Romans to be surrounded by mythological presences but even the general slaughter in Rome could not be built without his de antiquities flavored decoration.

Behind the majestic entrance, there is a 25000mq area that is considered one of the fundamental pieces of the Roman industrial archaeology, together with the close by dismissed Gasometer.

Today some parts have been restored and spaces used as headquarters of different activities, like a secondary branch of the MACRO (Museo di Arte Contemporanea di Roma).

[socialWarfare]