After the unification of Italy (1861) Rome becomes capital and consequently undergoes a profound urban transformation in order to adapt to this new role.

One of the important areas to be redesigned was the Esquilino neighborhood.

Gaetano Koch planned a large scenographic square (the biggest in Rome, bigger than St.Peter’s square!!) overlooked by prestigious palaces with large porticoes and a wide garden in the center that surrounded the remains of Alexander’s Nymphaeum. Like everywhere else in Rome during the excavation work, traces of an ancient cemetery were found where slaves and murderers were buried, together with a bunch of other Roman ruins.

The goal of the city plan drawn up in 1873, was to identify the new architecture with the Umbertino style (related to Umberto I, king of Italy between 1878 and 1900) that has characterized much of the Italian post-unification urbanism.

The square was naturally named after Vittorio Emanuele II even if the Romans confidently call it Piazza Vittorio.

Let me break this tale down with a short note: in Milan, nobody would ever dream of calling the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, “Galleria Vittorio” as if it were the uncle’s pizzeria. In Rome, however, that king imposed by Northern Italy must have be indigestible from the very beginning and this could explain such negligent confidence.

To the local population in 1883 when it was first inaugurated, the square must have looked like a huge modern alien, implanted in the baroque heart of the city.

(Immediately after the II World War in the arcades surrounding the square stationed a myriad of stalls selling everything that was possible to gather as portrayed in the film “Ladri di biciclette” directed by Vittorio De Sica)

In any case, the area chosen for this major operation presented many advantages compared to other central ones: it was close to the new Termini Station, it was not very urbanized and it was characterized by the presence of villas with vast gardens, vineyards and vegetable gardens.

One of the victims of the reorganization fury was Villa Palombara, a beautiful building dating back to 1680 that was brutally torn down to make space for the impressive reorganization desired by the new kingdom. A single door of the five entrances that served Villa Palombara was saved due to its esoteric meaning.

In fact the door was the entrance to the alchemical laboratory of the villa and on its sides two statues of the god Bes (an Egyptian divinity, considered the tutelary deity of the house, birth, and childhood), have been added, which originally belonged to the gardens of the Palazzo del Quirinale where in ancient times once stood a large temple dedicated to two Egyptian gods Isis and Serapis.

The owner of the villa was the Massimiliano Palombara, marchese di Pietraforte (1614-1680) who, like many other exponents of a small cultural elite, was an alchemist; he was also fascinated by the esoteric sciences, some of which he actively practiced.

His economic resources and his social position allowed him to finance a certain number of alchemists of his time. In his villa were held meetings attended by important personalities who shared his interests, including Queen Christina of Sweden, who lived in Rome after abdicating, the well-known astronomer Domenico Cassini, the distinguished scholar Father Athanasius Kircher and others.

Massimiliano Palombara was a member of the Rosicrucians and his practices were based on the concept that only initiated people could have access to the secrets of such knowledge.Therefore Villa Palombara was provided with a small separate annex, probably a laboratory, where the alchemical conventions and experiments could secretly take place.

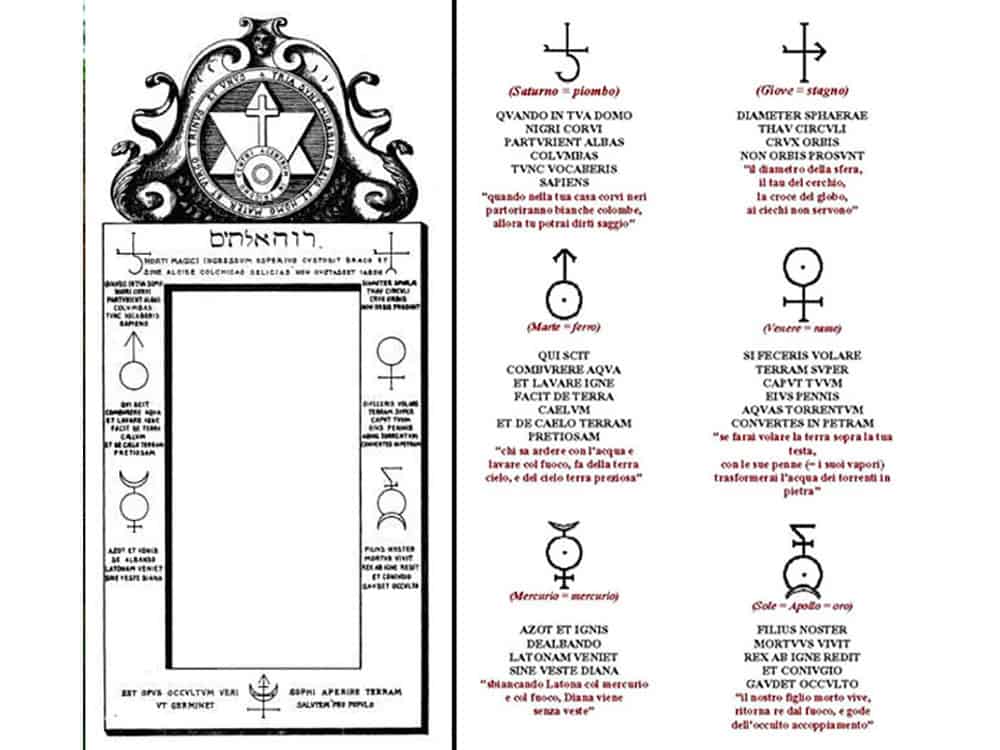

The door has many mysterious symbols and inscriptions carved into the stone: all this induce us to think that, in addition to physically accessing the special room, the Magic Gate may have also represented an ideal threshold that the adherents crossed to reach the highest level of purity of their soul, a condition which, according to the Rosicrucian principles, was a fundamental.

When I look at the large flocks of tourists who cross the city, exhausted by their long walks, overwhelmed by the number of ruins to see and the effort of finding their way through a maze that seems to have no sense, I wonder what kind of memory they will take home.

In order to avoid the melting pot effect, every time I go to Rome, I try to visit something new, inevitably linked to a great story, such as this stone door that with its mysterious signs keeps us tied to a time that it has swallowed through change and reconstruction.

It ‘a little tribute I pay to this incredible city that makes me fill it a bit closer and respectful to its infinite beauty.

Betti

[socialWarfare]