I confess I have a peculiar attraction for certain ancient aspects of sciences and anatomy study. What fascinates me most is the grace with which scholars of the past managed to represent their findings: every object, even the most macabre, was isolated and inserted into a reassuring context, with the obvious goal to deprive it of its scary and horrific potential.

Far from the aseptic style of the modern science approach, these expositions very rarely bother the viewer who, on the contrary, get close to the old wood and glass showcases and their contents, often made in a stunning realism, without even associating the beauty they are admiring with their direct provenience.

The visit we just did in Bologna to the rooms of anatomical waxes inside Palazzo Poggi has been enormously satisfactory from this point of view.

For much of the eighteenth century, the University of Bologna was considered one of the most advanced centers for the anatomical wax reproduction of figures or individual parts of the human body.

These reproductions had the advantage of studying the myriad of parts and structures of the body during any season and at any time of day without the inconvenience of the cadaver’s putrefaction and without fear of eventual contagion.

The most surprising thing is that a woman who we will mention later, a great scholar internationally recognized, was one of the most important exponents of this rare art, essential to medical research and study of the time.

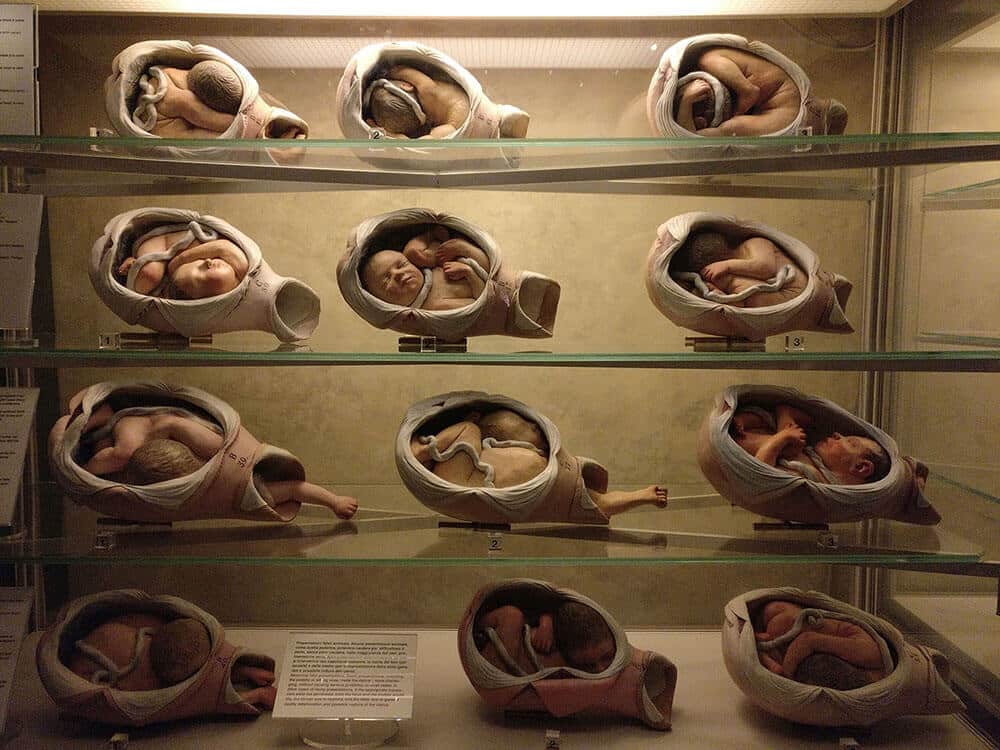

In the museum, you can visit a first room whose walls are completely covered with exhibitors in which are neatly lined up countless reproductions of opened wombs to show the visitors all the various positions a fetus can possibly take during pregnancy.

The author of the work I just described was Ercole Lelli who we already mentioned regarding the surprising sculpture we saw in the Anatomical Theatre and who collaborated in the middle of the 18th century with what we can consider the most amazing couple of anatomical artists.

When I say “couple” I just mean husband and wife and as we enter the second room we have the chance to meet Mr. Giovanni Manzolini and Mrs. Anna Morandi, reproduced in two life-size busts, with the techniques they employed to create their incredible sculptures.

In her wax self-portrait Mrs. Morandi dresses in rich eighteenth-century clothes, with her neck and wrists adorned with pearls, her head crowned by an unlikely old rose wig, suspiciously similar in color to the brain that peeps out of a skull leaning on a wooden stool between her chubby hands, under her indifferent gaze lost in space.

The full scene is pretty odd but perfectly represents an idea of decency and dignity that modernity has long abandoned.

After her husband’s death, Mrs.Morandi continued the activity of anatomical modeler on her own and her skill in anatomical wax design was renowned in academic centers all over Italy and Europe.

She received invitations from throughout Europe to relocate her practice and singular collection. It was precisely this outside notice and the potential risk of losing such a popular Grand Tour attraction that prompted Bologna’s cultural patriarchs to recognize her work formally with a small annual stipend and a university appointment in anatomical exposition.

We have to imagine what it meant for a woman of the 18th century alone to dissect cadavers just retrieved from the nearby hospital and demonstrate her wax studies of anatomy to crowds in her home studio.

Her peers and society ladies of the time, having received formal training, were devoted to singing, embroidery and fine arts. In fact, both Anna and her husband had started their careers following art studies but their domestic study became a room where they inspected muscles, nerves, and vessels, a legal medicine institute before anything like that ever existed.

One last surprise greets visitors at the end of the exhibition: the sculpture called “La Venerina”, a young woman lying abandoned on a satin cloth, surrounded by her organs, with the belly open made by Clemente Susini between 1780 and 1782.

In the history of the wax modeling, in fact, the representation of the female figure dissected, sometimes awake, sometimes dormant or moribund, showing, without shame both her nudity and the interior of her body, was very common.

These realistic and often sensuous statues of supine women are present in many collections of different countries and frequently are called anatomical Venus. One of the characteristics, they have in common is that they are often represented in different stages of pregnancy.

These true works of art with their sweet and often sensual expressions, had the merit of bringing the anatomy to the public, removing the macabre disgust arising from the presence of the corpse.

The reason why these wax figures were called Venere is quite clear: it was needed a perfect skin, an intact body which could be opened like a box (many of these reproductions had a removable belly that hid the dissected inside), revealing the anatomical secrets, but when the observation ended the wax corpse could return to its original beauty, to delight the eyes and the senses.

A statue that had an apparent ideal beauty that hid the secret of real flesh.

In front of the “Little Venus” we feel in the presence of a beauty in agony.

Females figures in the Italian anatomical Venuses always express the idealization of the agonizing death of a beautiful, young woman, capturing in this way the essence of Eros and Thanatos.

La Venerina is pretty small: 145 cm but was built by the author scrupulously copying the corpse of a young girl, who had died recently.

The statue is in fact extremely interesting from an anatomical point of view to the cause of death and the peculiarities of the disease. The body of Venerina is a faithful representation of a young woman who died during pregnancy, with the exception of the heart and major blood vessels. The ventricular walls are the same size, 32 mm, and equal thickness, 5 mm. In a normal heart, the left ventricle is three times thicker than the right.

Only two hundred years after the construction of the statue in wax, it has been discovered that the girl was suffering from a congenital heart disease which caused premature death and could have been due either to an endocardial infection or cardiovascular insufficiency, caused by the advance of a pregnancy.

I couldn’t tell if it was the somehow drowsy atmosphere of the museum, the languid pose of Venerina or her helpless look to make me dwell on her abandoned body, but I find it touching that only after two centuries the modern doctors, thanks to the meticulousness of Clemente Susini, have given a scientific explanation for the death of this young woman.

Betti

Palazzo Poggi Anatomical Waxworks

[socialWarfare]