Today, taking advantage of a cloudy day, we finally decided to visit the Civic Museums of Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza.

My goal was to see a very rare object that I’ve been always intrigued by: the Etruscan haruspical liver.

Piacenza, which has now become one of the most active logistics centers in Italy (Amazon has recently placed in the nearby countryside one of its largest storage centers in Europe), was identified by the Romans as a crossroads between Rome and Northern Europe well before the multinationals trades pointed their finger on its strategic position.

Placentia (that’s the Roman name) was founded in 218 BC as a Roman colony; located on the Via Emilia, it represented a very important military outpost against the advance of the visionary Hannibal who, at the end of that year 218, came from Carthage with his troops and his elephants through Spain and the Alps to conquer Rome.

This explains why in this area, as in many other places in Northern Italy, numerous finds from the Roman era have been found, but less explains the discovery of this very peculiar object.

A lot of mystery surrounds the history, customs, and characteristics of the Etruscan civilization as the interpretation of their language, essentially based on funerary finds (we have no literary finds), is still incomplete.

We know that their presence in Italy was spread out over a vast area that included Lazio, Tuscany, Umbria, and the Pò plain between the 8th and 1st centuries BC.

We also know that their civilization preceded and accompanied the Roman one for a long period until it disappeared, leaving traces on the territory, as we have said, mainly centered in the necropolis.

We also know that the Romans focused and obsessed on building, paving everything they had to walk on, and figuring out a legal system from which we still benefit today, were a little weak on the divinatory tricks.

For this type of duties, they turned with confidence to the Etruscans haruspico clan who had developed over the centuries the skill of clarifying the Gods encrypted intentions communicated to the poor humans with extraordinary and inexplicable facts.

Just to give an example, it is said that Julius Caesar’s personal haruspex, the Etruscan Spurinna, would have predicted the date of his tragic death.

But who were they and how did they enveil the messages sent by the gods? The word haruspico derives from the Latin HARUSPEX which means “the one who observes the liver” in fact their task was to explain the divine will through the analysis of the livers of the sacrificed animals.

(In case you want to specialize this activity is also called hepatoscopy.)

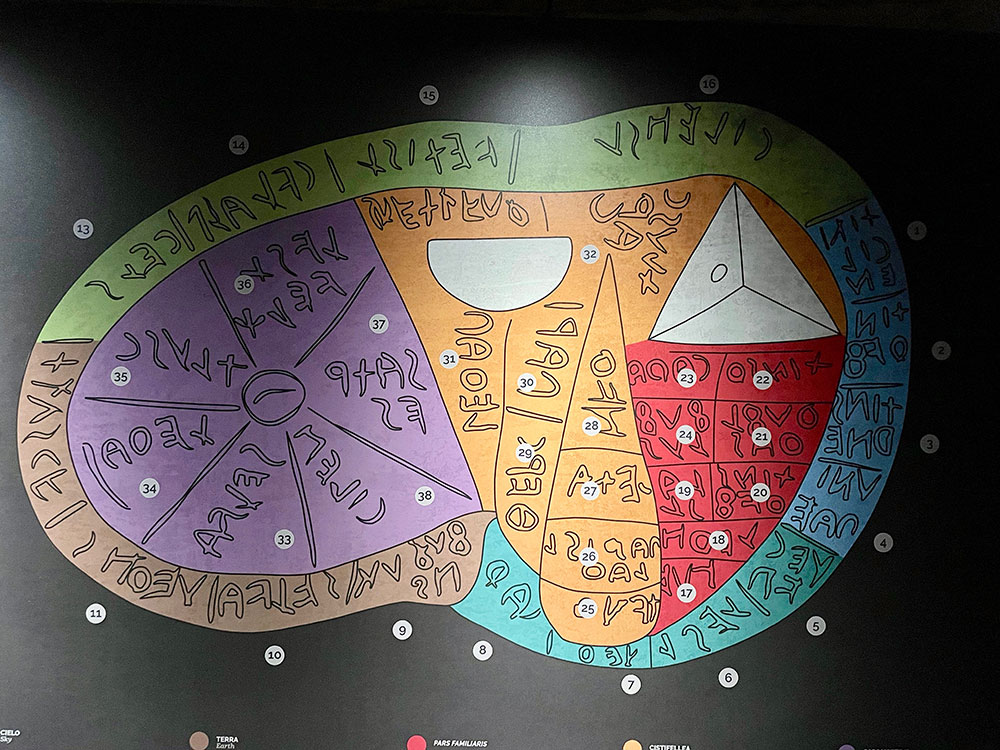

Following the law of the Microcosm and the Macrocosm (everything in the world is a Universe identical reflection), they studied the signs such as scars or other anomalies present in the small organ hypothetically divided into about forty sectors.

Each section corresponded to a precise God and the area in which the anomaly was identified signaled both the messenger and the divine message.

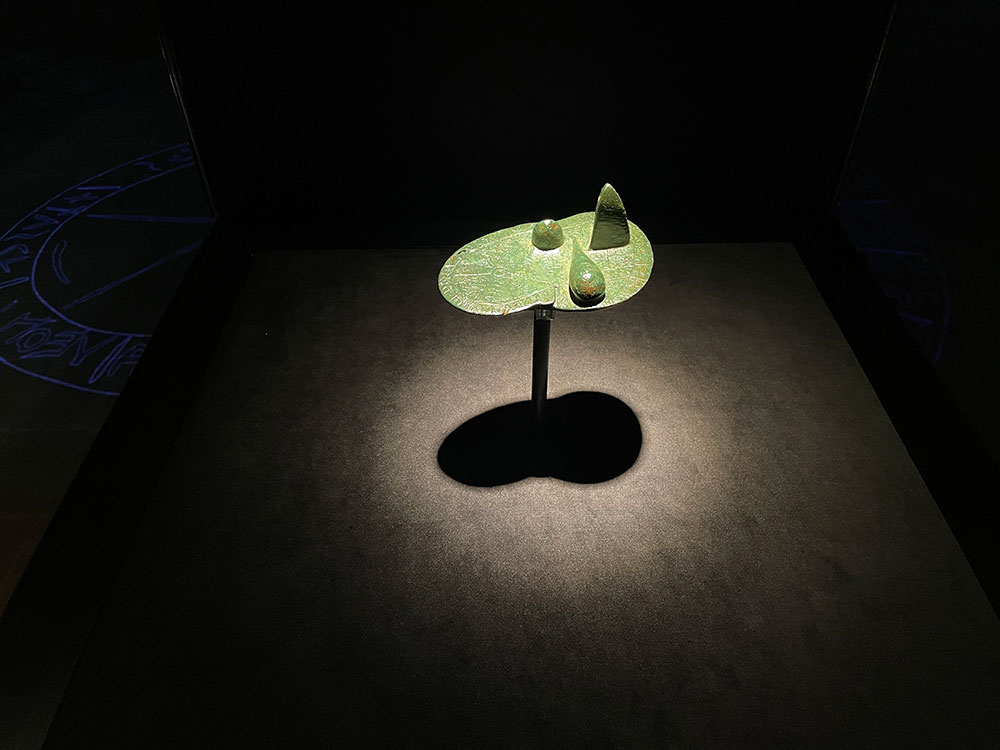

Of course, only members of the Etruscan aristocracy who passed the secrets from generation to generation could access this activity. The object that tickled my curiosity is an Etruscan bronze model of a sheep (or goat) liver which is located inside the Archaeological Museum housed on the ground floor of the Visconti citadel.

Perhaps the best known and most prestigious find in the civic collections was casually intercepted in 1877 in the Piacenza countryside by a farmer who was plowing a field.

In 1894, Count Francesco Caracciolo, who sensed its importance, acquired it and then donated it to the Piacenza civic collections.

Its destiny was to become the star of the museum, the best-known piece, and most prestigious find: a rare direct testimony of the religious practices we have mentioned.

Dated to the end of the 2nd – beginning of the 1st century B.C. it was probably meant to be a didactic aid for disciples-apprentices or a legend for that priests.

Even if it’s a relatively small object you can read inscriptions with the names of the 40 divinities: the order of the sky according to the Etruscans is practically reflected on its flat side.

Well, I thought I was the only one who had to write everything down!!!!!!

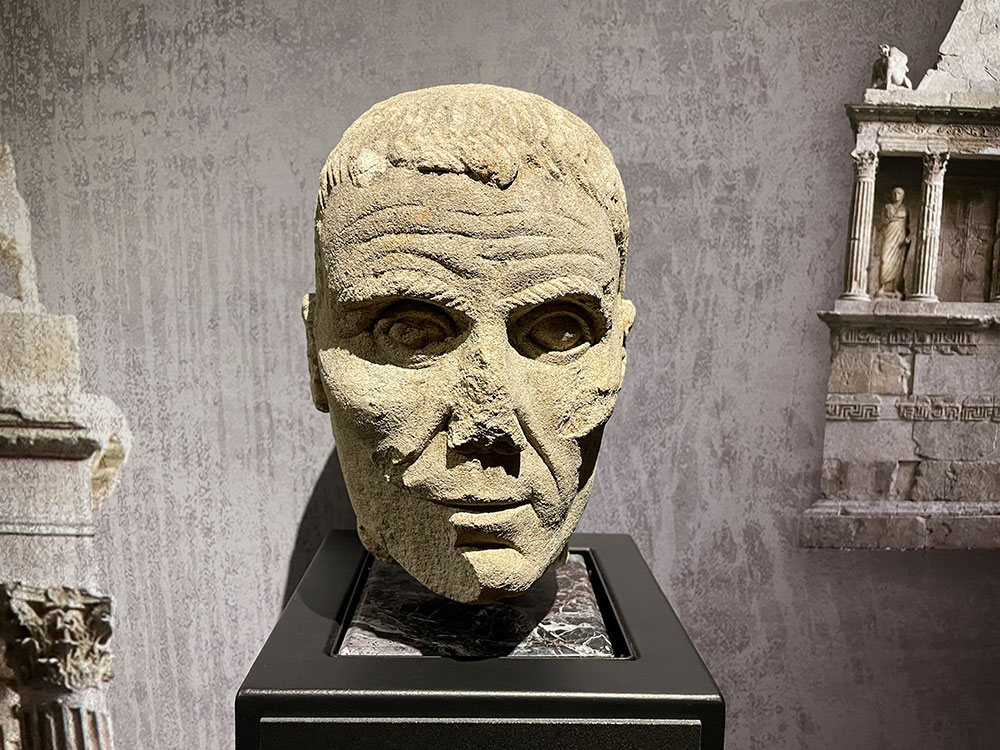

Needless to say, inside the Museum you will be able to see other very interesting finds that tell us more about our most remote past with artifacts from the ancient Paleolithic (about 400,000 years ago), to our “more recent past” the Neolithic (VI – IV millennium BC) …. a nice journey through time!

When I was a child people were asking me about the job I would have a pick in the future: my answer was either the hairstylist or the archeologist…. I somehow managed to make my dream came true by becoming a make-up artist and this kind of visit pay off for the second choice!!!

Betti

[socialWarfare]