On March 16th, 1978 (40 years ago) Aldo Moro, Secretary of the Christian Democrats, jurist, and member of the Constituent, 5 times President of the Council of Ministers, is kidnapped and after two months killed in Rome by the Red Brigades.

In Italy, these are the years of terrorism and the fight against politically extreme groups. On April 14th, 1982, the first trial for the abduction and killing of Mr. Aldo Moro begins in the bunker room of the Foro Italico.

The hall destined to host one of the historical trials of this country is set up inside a structure evidently considered of little architectural interest: The House of Arms of the Foro Italico in Rome.

The building is readapted with a heavy protective gate so as to avoid assaults or acts of terrorism during the trials and it remains as such for the next 40 years.

Considering that in the ‘80s the authorities wanted to demolish the Casa del Fascio designed by Terragni (See our previous article at this link) and only the intervention of Bruno Zevi blocked the destruction of one of the most important testimonies of Modern Italian architecture, one realises of aversion that had developed in this country against a style inevitably linked to the historical period that produced and supported it.

The years pass, the phenomenon of terrorism is circumscribed and annihilated, society changes, ideologies collapse and the denial on the part of art historians regarding the rationalist architecture, typical of the Fascist era, starts softening.

The Casa delle Armi is one of the buildings of the Foro Italico, the vast sports complex designed by Enrico Del Debbio at the foot of Monte Mario in Rome and inaugurated in 1932 under the name of Foro Mussolini.

The project of the Fencing Academy, originally called the Casa del Balilla Sperimentale, was entrusted in 1933 to the young architect Luigi Moretti, who had just replaced Enrico Del Debbio in the direction of the technical office of the National Balilla Opera. Mussolini, himself, inaugurated it three years later with the name Accademia fascista di Scherma(Fascist Academy of Fencing).

The structure is located towards the southern end of the Foro Italico, just beside the Tiber river and close to the new Ponte della Musica. It was part of the great fascist project which was meant to guarantee a devoted youth through the dissemination of sports facilities. It also promoted through its architecture its philosophy, which was based on the cult of physical prestige and adherence to the dictates of the regime.

As I said before it has been used for very different functions from those for which it was intended (first as a judicial bunker hall and later as carabinieri barracks).

Today it is a structure managed by CONI (Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano) and is rightly considered among the testimonies of excellence of Italian rationalism.

The Academy is made up of two orthogonal structures designed to house multi-purpose spaces: the Library and the Arms Room. The two buildings are joined by an elliptical structure and connected through two aerial passageways.

All external surfaces are clad in white Carrara marble slabs. The Library was conceived as a vast room overlooked by two overlapping galleries which were intended for reading, these aerial areas in the space are visible from the entrance and illuminated by a huge window which opens to the Forum.

The other building, the large Sala d’Armi, which would have permitted the exercise of 160 simultaneous fencers, is covered by two staggered parabolic elements of reinforced concrete which are connected by a long frame; the large windows, both the environment with diffused light that further expands the space.

The short side facing the Tiber is bipartite: half blind and marked by a horizontal giant window grate for the other half. The second part, which is 45 meters long and 25 meters wide, hosts the fencing room indicated above.

The statuary marble cladding of Carrara chosen by Luigi Moretti contributes to enhancing the elegance and purity of the volumes.

It is said that the search for formal perfection for this building led Moretti to apply the marble slabs exclusively at night, so that, through an artificial light grazing the wall, you could see better and eliminate all imperfections.

The immense space is immersed in which light creates a metaphysical, rarefied, solitary environment and its vastness, typical of celebratory architecture, takes on a more cultured and polite, almost cinematic note in this environment.

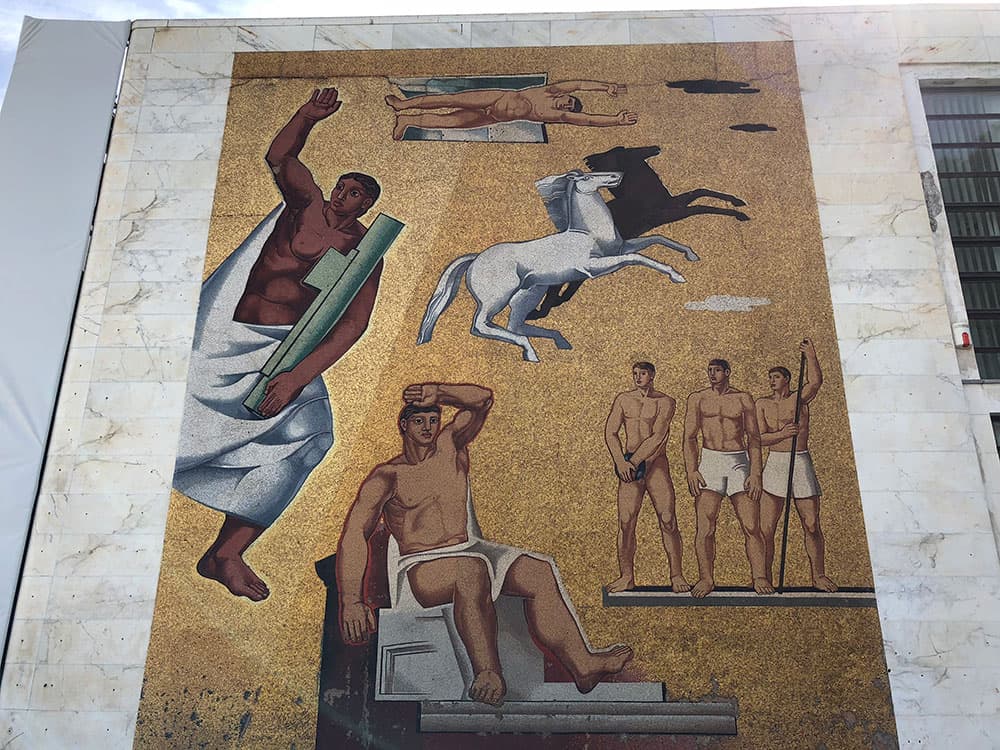

Another loquacious presence in this avant-garde architecture is represented by the enormous mosaics typical of the period: we find one on the outer wall of the Library wing, realized on designs by Angelo Canevari.

On a golden background stands the most imposing figure, the Vittoria Littoria, seated on a throne in the act of making the Roman salute with her right hand, and with her left hand engaged to hold a beam and then Icarus, under him the two horses of the Sun and alongside three athletes caught in a moment of rest, and finally an allegorical figure, sitting on a bench representing the Italic Genius.

In the Fascist era, the mosaic walls, in addition to ideally reconnecting with the great tradition of the Roman marble mosaic, were chosen for their durability, their majesty and perhaps even a certain expressive rigidity that matched the will to illustrate a strong, society capable of submitting to strict rules and at the same time moved by the enthusiasm and belligerent optimism typical of the Twenties.

In most of the rationalist works, we find allegorical representations in mosaic and this technique has in a certain sense illustrated and still reminds us of the ambitions of grandeur typical of the time.

This is precisely the feeling that is felt in observing this architectural object finally revalued and reconsidered: the admiration for that ability to perceive modernity (when Moretti was commisioned with carrying out the project he was just twenty years old), to know how to interpret the appearances, construct its symbolic space and on the other hand the skepticism of history which brutally reduced every ambition.

The city of Rome has resisted the will to forget the dictatorship through the destruction of its exterior symbols as has often happened in the rest of Italy and today we are perhaps a little grateful to have access to a piece of our history that would otherwise have gone lost.

I admit that I came to see this little gem only after countless visits to the city but I invite anyone interested in modern architecture not to miss a visit to the Foro Italico: a different Rome, outside of the beaten track.

Betti

How to get there:

[socialWarfare]