On June 12, 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte signed the “Edit of Saint-Cloud“, which established the birth of modern cemeteries and regulated burial practices once and for all. The purpose of this law was evidently hygienic-sanitary, as cramming the bodies of the deceased in churches (in order to keep the bodies near the relics of saints and martyrs) and in common pits (mass graves dug inside city walls where, for example, during the plague, the bodies of the dead and dying infected were thrown) caused the spread of horrendous and extremely dangerous diseases.

According to the edict, cemeteries had to be built outside the city walls, at least 35-40 meters away, preferably on sunny and airy land. With the fall of the Napoleonic Empire, the ban on personalizing tombs and headstones fell as well, and above all, the emerging bourgeois class, which did not have family chapels, pushed the political power to leave margins of freedom in the choice and construction of tombs and headstones.

In France, in the first half of the 19th century, the first monumental cemeteries were born, adorned with monuments and large sculptures, and all the European capitals began to equip themselves with equally symbolic and spectacular burial places, such as Père-Lachaise and Montmartre cemeteries in Paris, Dorotheenstadtischer Friedhof in Berlin, San Isidro Cemetery in Madrid, Kerepesi Temeto in Budapest, and Brompton Cemetery in London. In Italy too, many monumental cemeteries were born in the 19th century (including the one in Milan, which we will talk about someday), and today we visited one, particularly large and characterized by a slightly neglected appearance that, as far as I’m concerned, greatly increases its charm: the Staglieno Cemetery in Genoa.

Its vastness makes it one of the most important cemeteries in Europe, and among its walls, illustrious figures are buried, including one of the fathers of Italian homeland, Giuseppe Mazzini, as well as patriots, singers, artists, actors, and one of our most beloved singer-songwriters, Fabrizio De Andrè.

The design was entrusted in 1835 to the architect Carlo Barabino, who died in the same year due to the cholera epidemic that had hit the city; the project passed to his collaborator and student, Giovanni Battista Resasco, and the structure was opened to the public only on January 2, 1851. Today, the cemetery covers an area of approximately 330,000 square meters and also includes a section dedicated to the English (where Constance Lloyd, Oscar Wilde’s wife, is buried), one for Protestants, and a Jewish area.

The first image that greets you at the entrance is a huge statue representing Faith, nine meters high, and behind it, at the top of an imposing staircase, is the Pantheon building (a copy of the Pantheon in Rome) with its Doric columned portico and dome.

From this classical reference onward, it is all a riot of styles and overlaps, ranging from Gothic to Byzantine, from Neo-Egyptian to Liberty, from Mesopotamian to Neoclassical. The Genoese bourgeoisie plays for fame and recognition in this apparently lifeless place to which a very important task is entrusted: to remember for posterity the value that is civic or economic, little does it matter.

The new ruling class, the new entrepreneurs, the new powerful people want the memory of their lives to pass on to posterity, and to achieve this, they build imposing, convoluted tombs.

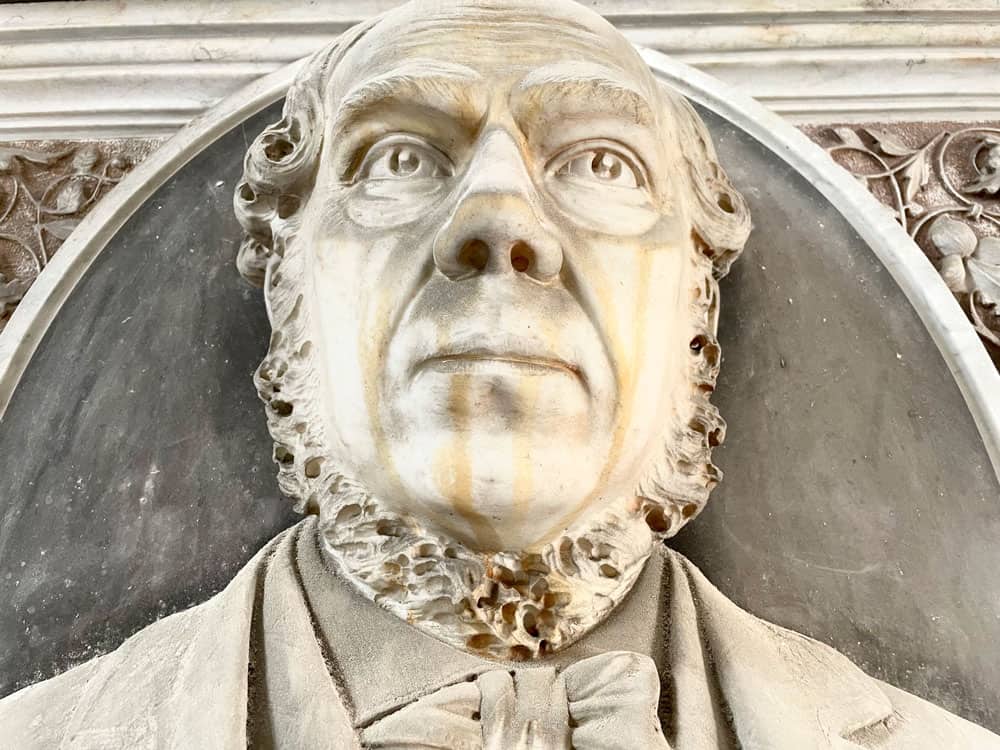

They had themselves portrayed while still alive, showing in detail the tools of their success, the details of their clothing, and the severity of their characters. The prominent Genoese families focused on Staglieno and their own burials to strike the citizens’ imagination with the same determination that the nobles once represented themselves on equestrian statues and in family chapels. They perhaps used a less lofty and more everyday lexicon, certainly without embellishing themselves too much, but it had to be clear to everyone who was driving commerce and who had an important role in society at the time.

I have always had a particular passion for cemeteries, and in every country in the world I have visited, I have wanted to visit one of its cemeteries: the way we bury the dead speaks much more about us than we want to think.

It is curious, for example, to see how the iconography of the tombs of the mid-1800s reflects the bourgeoisie’s self-assurance, its values, and its unstoppable climb to the top of society. Men and women appear firmly planted on the ground, in flesh, the sculptor lingers on the imitation of details, folds of clothing, and marble pierces the lace of women. Descriptive realism does not give rise to thoughts, transporting the subject represented directly into the eternal dimension.

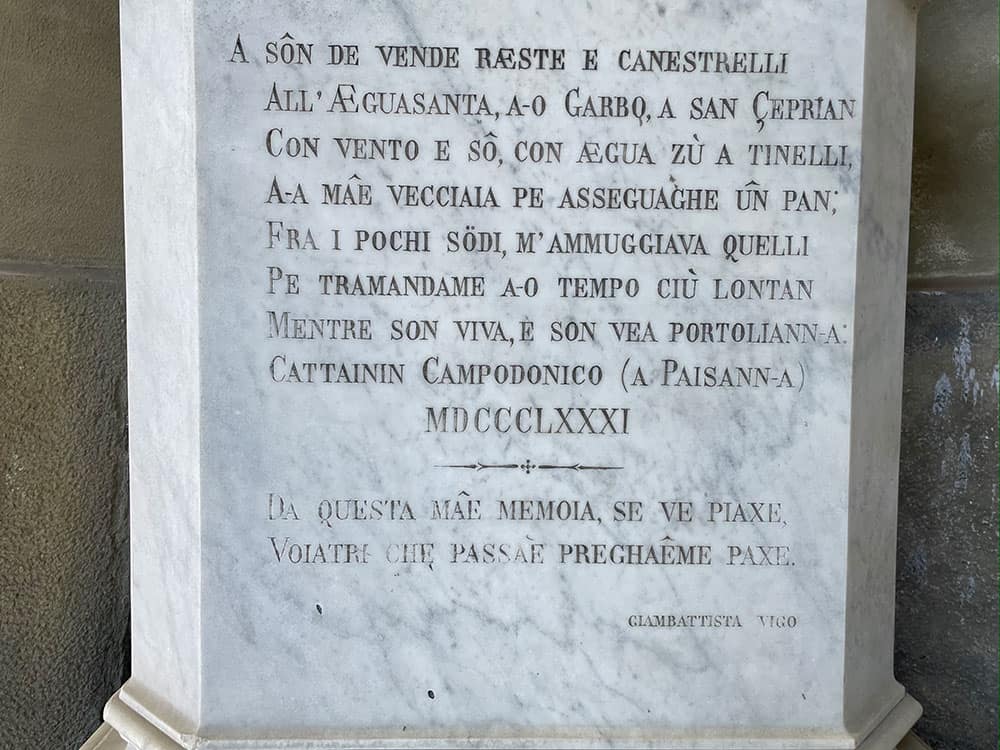

Even the common people adhere to this desire for eternity. One of Staglieno’s most famous funerary statues, the statue of the hazelnut vendor (Caterina Campodonico), is an example of this, an elderly street vendor who saved pennies throughout her life to be portrayed still alive by one of the most fashionable sculptors of the moment.

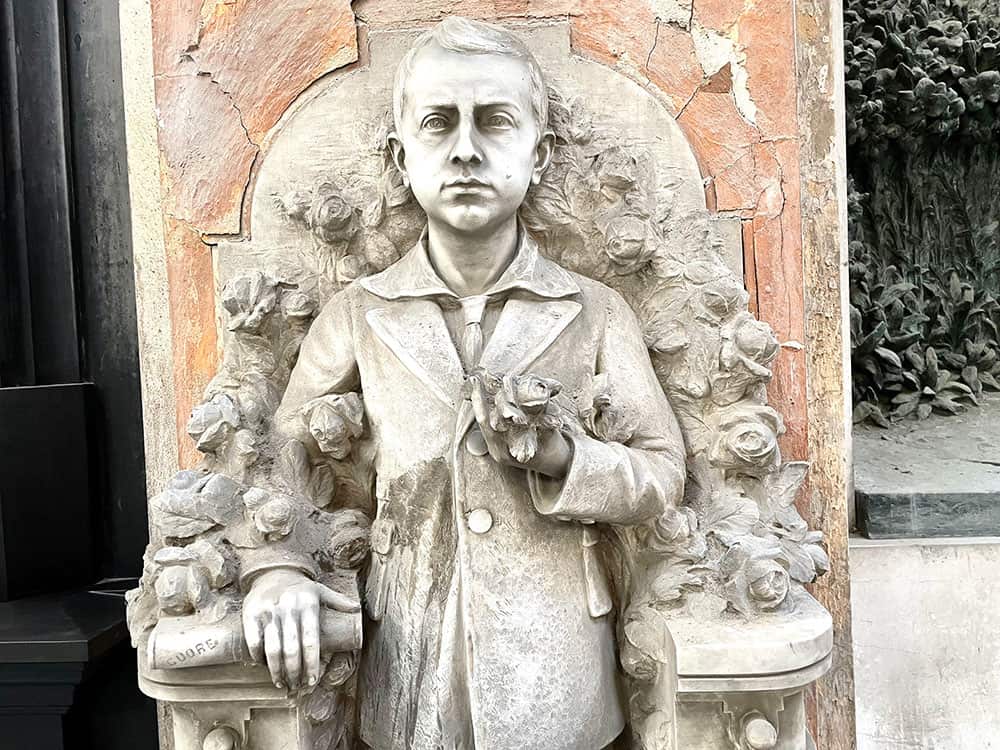

A few decades later, some doubt creeps in, and symbolism and the pre-Raphaelite style arrive at the cemetery with their charge of indecision, doubt, and melancholy. The era of certainty and solidity has ended, and the sculpture of the thoughtful androgynous angel, commissioned to Giulio Monteverde by Francesco Oneto, a wealthy merchant and president of the Banca Generale, definitively deviates the current aesthetic towards new visions.

The statue, strongly criticized and censored, actually had enormous success and was replicated countless times both in Italy and in Europe and overseas.

The images that we propose represent a tiny fraction of the curiosities, beauties, exaggerations, intimacies, and surprises that you can find in this place of wonders: take a day as we did, bring a snack, sit down every once in a while, and absorb the smell of freshly cut cypress trees. Take photos, get lost in the alleys, be curious, try to understand what those people wanted to tell you.

And here I stop, I won’t tell you more: you will be amazed at how much life there is within the walls of a place meant for people resting in their eternal sleep.

Betti

If you plan on visiting here is the official web site of the cementary: http://www.staglieno.comune.genova.it/

Along with the map to get there:

[socialWarfare]